Genpei Akasegawa

Genpei Akasegawa is a rare phenomenon, an artist who successfully transitioned from the avant-garde to the larger realm of popular culture. He emerged on the Japanese art scene around 1960, starting in the radical “Anti-Art” movement and becoming a member of the seminal artist collectives Neo Dada and Hi Red Center. The epic piece Model 1,000-Yen Note Incident (1963-1974), which involved a real-life police investigation and trial, cemented his place as an inspired conceptualist. His irreverent humor and cunning observation of everyday life made him popular as a writer, peaking with his 1998 book Rõjinryoku, in which he put forth a hilariously positive take on the declining capabilities of the elderly. Hyperart: Thomasson, marks a crucial turning point in his metamorphosis from a subversive culture to a popular culturatus.

books

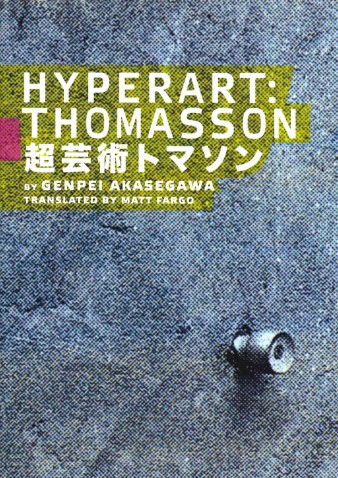

Hyperart: Thomasson

Pre-order revised edition here, forthcoming fall 2025.

We are releasing an updated version of this book! In this revised edition, Matthew Fargo’s original US translation of Akasegawa’s hilarious, brilliantly conceived exercise in collective observation is accompanied by reflections from noted scholars Jordan Sand and Reiko Tomii, as well as a new essay by Akasegawa scholar William Marotti and a reflection on Akasegawa’s legacy as a teacher by writer, artist, and composer Masayuki Qusumi, a former student of Akasegawa’s.

Have you ever seen a Thomasson? That doorknob in a wall without a door, that driveway leading into an unbroken fence, that strange concrete … thing sprouting out of your sidewalk with no discernible purpose. Have you ever puzzled over its strangeness, or stopped to marvel at its useless beauty?

In the 1970s Tokyo, artist Akasegawa Genpei and his friends began noticing what they termed “hyperart,” aesthetic objects created by removing a structure’s function, while carefully maintaining the structure itself. They called these objects “Thomassons,” after an American pinch-hitter recruited by a Japanese baseball team, whose bat never connected with a ball.

In the 1980s, through submissions from students and readers, Akasegawa collected and printed photos of Thomassons in a column in Super Photo Magazine. He wrote these columns with a warm, goofy humor that seems intended to cast back nihilism, irony, and other common responses to 20th century urbanization. What emerged was a lighthearted, yet profound, picture of how modernization was changing Japan’s urban landscape, and the culture that underpinned it.

These columns, collected into a book, became a cult hit among late-eighties Japanese youth. What they saw in this assemblage of casual photos and humorous descriptions was, as essayist Jordan Sand puts it, “a way of regaining some sense of the human imprint on the city in an era when that imprint was being rapidly erased.”

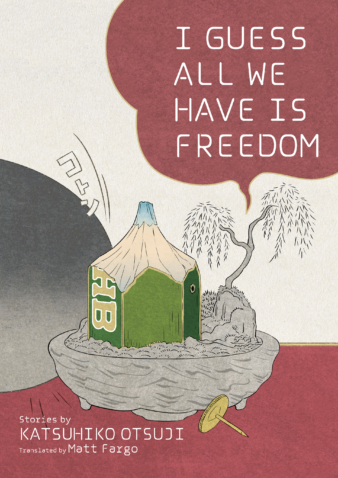

I Guess All We Have is Freedom

Gravestones hatch political critiques and tomatoes resist being eaten in the wildly surreal and funny stories of Genpei Akasagawa, a giant of the Japanese avant-garde

There is a small but potent club of authors―Miranda July and Patti Smith are both members―who were renowned artists long before they became writers. Genpei Akasagawa, writing under the pen name Katsuhiko Otsuji, was already a giant of the Japanese contemporary art world when he began writing these stories, which earned him Japan’s two most prestigious book awards.

In these stories, ostensibly quiet tales of a single dad in 1970s Tokyo, a doorknob practices radical politics, a peeled tomato smarts in pain, raw oysters tick like time bombs and gravestones provide a critique of capitalism. After reading I Guess All We Have Is Freedom, you will never be able to look at a sliding door, a rubber band or a plastic gutter the same way again. In spite of their suburban settings, the stories here are more radical than the most cosmopolitan contemporary art. Or as the protagonist puts it: “The whole art thing is a little played out at this point. Nowadays, it’s all about buying gutters. Going out to buy a gutter on a sunny day.”

Genpei Akasegawa (1937-2014) was a rare phenomenon, an artist who successfully transitioned from the avant-garde to the larger realm of popular culture. Akasegawa emerged on the Japanese art scene around 1960, starting in the radical Anti-Art movement and becoming a member of the seminal artist collectives Neo Dada and Hi Red Center. The epic piece Model 1,000-Yen Note Incident (1963-74), which involved a real-life police investigation and trial, cemented his place as an inspired conceptualist. Hyperart: Thomasson (Kaya Press, 2010), a collection of musings on art that the city itself makes, marks a crucial turning point in his metamorphosis from subculture to pop-culture status. Also an accomplished author writing under the penname Katsuhiko Otsuji, in 1981 he won Japan’s most prestigious literary award, the Akutagawa Prize, for his story “Dad’s Gone,” translated into English here for the first time in this volume.

praise

“Mr. Akasegawa is the kind of artist who inspires everybody every time he makes a new piece of art.”

— Yoko Ono

“Why is the city always laughing at us behind our backs? Akasegawa, of course, knows the answer, but prefers to keep us prisoners of his enigma…” — Mike Davis, author of In Praise of Barbarians

“An indispensable, hilarious, and faux-naïve map of postwar Japan, conceptual art making, and exactly that point in the ’70s where Western consumerist culture collapses into unapologetic simulacra. Let this witty master of resistance usher you onwards to genuinely useful modes of higher observation … until one sees and knows only the startlingly different.” — Michael Light, author of Full Moon and 100 Suns

“I Guess All We Have Is Freedom is a sly and playful book that unfolds through objects and feelings, and the movement of lizards and trains. At times it is tender and melancholy, at others irreverent and enigmatic. It is always very pleasing, and profoundly good.” —Amina Cain, A Horse at Night

“Like all good poetry and all good humor, Genpei Akasegawa’s brilliant short stories tear the world apart and build it anew.” —Julia Kornberg, Berlin Atomized

Genpei Akasegawa news

On Sunday, the 26th October of 2014, renowned Japanese avant-garde artist and writer Akasegawa Genpei passed away in Tokyo, leaving behind an inspiring legacy. His literary works include Rōjin-ryoku and Hyperart: Thomasson, the latter of which we published in English in 2010. Read words from our publisher & our translator here. Here are some photos in memory of Akasegawa. […]

On Sunday, the 26th of October, 2014, renowned artist and writer Akasegawa Genpei (赤瀬川 原平) passed away in a hospital in Tokyo. Akasegawa was the author of Hyperart: Thomasson, which Matt Fargo translated and Kaya Press published in 2010. Best known for his avant-garde art and involvement with Neo-Dadaism, he co-founded the Hi Red Center in 1963 […]

99% Invisible, a radio show about design and architecture, recently featured our book HYPERART: THOMASSON by Genpei Akasegawa on their show, with a companion piece on their blog, along with the book’s trailer: Here’s an excerpt, and you can listen to the full episode here. “Akasegawa started noticing similar urban leftovers, and treasured them as […]

They’re both part of The Believer‘s 2013 Art Issue! Along with cover art by J. Otto Seibold of children’s book Lost Sloth, the November/December issue includes a review of Kaya book Hyperart: Thomasson. Read an excerpt of the review, written by Daniel Levin Becker, here.