Welcome back to THROUGHLINES, Kaya Press’s newsletter that bridges the gap between contemporary Asian Pacific literature and Asian American Studies. In our seventh issue, Neelajana Banerjee, shares her syllabus for her Introduction to Asian Pacific American Literature class. Our running inventory grows with its seventh installment, highlighting recent publications by API diasporic authors. Nicole Chung also offers insights on how her debut memoir, A Living Remedy, can be read in classrooms for the fifth installment of our author interview series. She also offers her own reflection and insights on the intersection between her role as writer and professor. In the third installment of our series Endnotes, we compile trending media relevant to contemporary Asian American literature and culture. You can find updates on Kaya Press’s newest release, The Girl Before Her, and information on how to obtain desk copies at the end of this newsletter.

If you have questions or comments for THROUGHLINES, we invite you to email us at neela@kaya.com

Syllabus: Introduction to Asian Pacific American Literature

Neelajana Banerjee, Loyola Marymount University

Neelajana Banerjee teaches writing and publishing in the Asian American Studies Department at UCLA, and at Loyola Marymount University, and through private writing workshops. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University, and a BA in English and Creative Writing from Oberlin College. Her journalism has appeared on Teen Vogue, The Aerogram, The Center for Asian American Media Blog, LA Review of Books, Alternet, WordRiot, Colorlines, Fiction Writers Review and more. For a full bio, visit her website here.

I’ve been teaching this Introduction to Asian Pacific American Literature class at Loyola Marymount University since Fall of 2020, so going into my fourth year. It is a survey Asian Pacific American Studies course, but also fulfills a Creative Experience requirement, so attracts lots of non-majors (read: Finance and Economics and Entrepreneurship majors), so I see it as a crash course in Asian Pacific American themes and literature and offer up older / canonical texts next to newer authors and media. We circle questions like: Who has the right to tell our stories? What are the themes that go across all types of Asian American literature, and American literature in general? Do American readers and the mainstream publishing industry favor stories of trauma? Student groups lead presentations of the material each week, and along with discussing author context and themes–they are tasked with leading the class in a Creative Engagement–a writing prompt or discussion or something more exciting! Since it is a Creative Experience course, along with one analytical paper, the main writing assignment is a Creative Writing paper, and revision of that paper based on the themes of Asian Pacific American Literature.

Week 1: Angel Island Poems

In the first class, along with brainstorming what Asian Pacific American Literature is, we also watch some of this video about the history of the Angel Island Immigration Station, then read the Introduction and a few poems from Jeffrey Thomas Leong’s Wild Geese Sorrow: The Chinese Wall Inscriptions at Angel Island. Then the students write their own one line poems in response to the Angel Island Poems, about their own immigration history, or family hardship or even about a time they have been stuck waiting – waiting on a college admission letter, waiting in traffic (I am teaching in LA) – and students write a line on the board to create our own Angel Island poems.

Week 2: No No Boy

We then read John Okada’s No-No Boy, and I really push the students to put themselves in Ichiro’s shoes – would they make the choice he did, or would they make the easier choice and go to war? Along with this, we read Catherine T. Ramirez’s “The Moral Economy of Deservingness, from the Model Minority to the Dreamer” from her great book Assimilation: An Alternative History– her essay gives great contextualization to something that comes up again and again: the Model Minority, it also models how to write analytically about a text.

Week 3: When the Emperor Was Divine

While it means we spend some extra time on Japanese internment, I like to then have students read When The Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otuka, because the style of this book–each chapter written in close-third person from a different character’s POV in one family that experienced incarceration–is really informative to young writers. When – later – students are working on their own writing, I find myself often referencing Otsuka’s craft.

Week 4: The Woman Warrior + Jenny Zhang

I remember reading The Woman Warrior in an English class in my first year at Oberlin in 1996! Is it still relevant today? I am not sure but the hybrid style still challenges students and introduces them to intersectionality in a way that seems useful. What I have found really interesting is reading The Woman Warrior next to Jenny Zhang’s short story “We Love You Crispina” from her collection Sour Heart which opens with a visceral description of the titular character Christina having to defecate in a gas station bathroom in Bushwick, and details her Chinese immigrant family’s economic instability. Both these texts are about the plight of Chinese American second generation girls, but published 40 years apart. Are they in conversation – a great topic of discussion.

Week 5: David Tung Can’t Have a Girlfriend Until He Gets Into an Ivy League College & Nora From Queens Pilot

So many students can relate to Ed Lin’s YA novel about David Tung, a high-achieving student at an Asian American majority high school in suburban New Jersey. The full novel is long, so I have students read the first five chapters in which David spends a stressful day at school and a more fun one with his real friends at Chinese Saturday school in New York’s Chinatown. I like to pair this reading with the Pilot of Nora From Queens, in which Awkafina really leans into being anti-Model Minority. My favorite is a scene in which Bowen Yang plays her cousin in town from Palo Alto. I also use this week to share excerpts from Racial Melancholia, Erin Khue Ninh’s amazing Passing for Perfect: College Imposters and Other Model Minorities, and of course to talk about Affirmative Action.

*3 page close-reading paper due this week. I encourage students to focus closely on one text and one idea, working with them on organization and clarity.

Week 6: Dictee

So, curve ball: I force my undergrad, non-Asian Am / non-Humanities majors to read Theresa Hak-Kyung Cha’s experimental, fragmentary Dictee. Hopefully at least one or two a semester will have a moment of understanding and seeing the possibilities and open their minds to different ways of communicating ideas of war, identity and imperialism. After students have encountered the work and engaged with it, we read Cathy Park Hong’s “Portrait of an Artist” essay from Minor Feelings, and some other more explanatory work, like Mayukh Sen’s piece in The Nation, or this wonderful Folio in Yale Review–especially Ken Chen’s introduction. I am always heartened by the student presentation work on Cha and Dictee!

Week 7: Cathy Park Hong vs Jay Kaspian Kang & Adoptee Lit

This week students read Hong’s essay “United” from Minor Feelings against Jay Kaspian Kang’s “The Myth of Asian America” from the NY Times Magazine or as excerpted from The Loneliest Americans, and debate about what these authors are saying about Asian American identity. We also read a selection of Adoptee Lit, like Matthew Salesses’s essay on Matthew Selesses’ essay on Jeremy Lin, an excerpt of Nicole Chung’s memoir, All You Can Ever Know, and the amazing Alice Sola Kim horror story “Mothers Lock Up Your Daughters Because They are Terrifying”, which is published in the anthology Go Home.

Week 8: Carlos Bulosan and Elaine Castillo

In keeping with the ways early Asian American lit is influencing the new, we read some excerpts of Bulosan’s America is in the Heart, especially focusing on moments when protagonist Allos leaves the Philippines and arrives in the US, then move to an excerpt of Elaine Castillo’s America Is Not the Heart–particularly the opening prologue, a fever dream of a character’s life told in bold second person. [Full disclosure: I tried to teach this novel the first time I taught this course, and it’s length and difficulty made it an utter fail, though I have Filipino students eager to read about themselves. I mostly chalk it up to this exhausted time in the semester. It is one of my favorite novels of the past few years though!] We also read Castillo on Bulosan in the Nation, and some excerpts from her amazing How to Read Now, in which her bold and direct voice energizes students even at this challenging time in the semester.

Week 9: Focus on Filipinx Poetry

Again, due to the utter exhaustion at this time of the semester, I have learned to pivot to readings that we can focus on in class, and therefore have turned to poetry. I share selections of poems by Filipinx authors like Barbara Jane Reyes, Patrick Rosal, Kay Ullanday Barrett, and Chris Santiago. I find that students often have a resistance to poetry, so I like to share this NPR segment to help their process.

Week 10: 99 Nights in Logar

In the final portion of the semester the idea of older / canonical work influencing newer work falls apart a little, and I find that we end up spending more time talking about history in its place more than literature. I tried to read Bharati Mukherjee short stories or even Jumpha Lahiri, but didn’t find it connecting to the new work in a way that engaged students. So, we watch an excerpt from Valarie Kaur’s documentary Divided We Fall: America in the Aftermath that she made after 9.11 and some of her writing from her See No Stranger. Then go into Kamil Jan Kochai’s 99 Nights in Logar, which is an incredible novel that talks about War, immigration, Muslim American culture, American imperialism, but maybe most relatably: what it means to return home as an immigrant; set in Kochai’s ancestral village of Logar outside of Kabul and set in 2004.

Week 11: 99 Nights in Logar and The Homecoming King

I try and really slow down an make sure everyone reads as much of 99 Nights in Logar as possible so give lots of time at this point in the semester, as Kochai makes a really inspiring choice to put an entire culminating chapter of the book in a different language, which is an answer to a question that we have been asking throughout the semester at this point: which is – what is the cost of telling our stories as Asian Americans and immigrant writers? We also watch excerpts of Hasan Minhaj’s The Homecoming King to talk about some of the same ideas of 9.11 and how it affected South Asian Americans, especially Pakistanis and Muslim Americans.

*Creative Writing Assignment:

This is when the second major assignment is due – A Creative Writing prose paper inspired by the themes of Asian Pacific American literature that we have read. I try and make the assignment broad to see if the non-Asian Pacific American students take the bait and connect to the themes of the literature, which are about alienation and feeling left out and love and relationships with parents, etc., basically the themes of all great literature. They usually don’t and try to suggest papers like interviewing their Asian American roommates, and I have to redirect to ways they have connected in their own lives or how they can tell a story with those themes.

Week 12: “On Victims and Voices” and The Best We could Do

We kick off this week with a discussion of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s chapter “On Victims and Voices” from his scholarly book on Vietnam, Nothing Ever Dies. An excellent work that clarifies – again – those questions of who we are as immigrant writers, especially when the idea of refugee is introduced. I also show the “Battle of the Valkyries” scene from Apocalypse Now, and ask them to look at the faces that they see. If there is time, we also read Nguyen’s short story “Black-eyed Women” from The Refugees, available here.

Week 13: The Best We Could Do

This week, we read Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do, but use it as a way to talk about ways to read graphic memoirs and narratives, and POV and stories. It is a relief to read a graphic memoir at this late point in the semester.

Week 14: Afterparties and The Donut King

Finally, we watch the incredible documentary The Donut King, which is an amazing discussion of Cambodian genocide and Asian American small business. Then read a few of Anthony Veasna So’s short stories from Afterparties, including “The Women of Chuck’s Donuts,” “Superking Son Scores Again”, and “Maly Maly Maly”.

Week 15: Wrap up / Reading

For a final class, students read a paragraph from their creative writing papers to mirror our Angel Island Poems from week one. I also work closely with students to revise their creative writing papers and submit them for publication to the LMU Creative Writing journal or other creative writing journals available for first time writers.

A List of Recent Books from API Diasporic Writers, January 2023-August 2023

This incomplete list is one in a series of inventories THROUGHLINES is developing as an informal resource for students, researchers and writers to find adjacencies among established and new writers alike. For an updated list of titles, visit: http://kaya.com/throughlines/inventories/.

Poetry

From From – Monica Youn

Bianca – Eugenia Leigh

Return – Emily Lee Luan

Aina Hanau Birth Land – Brandy Nalani McDougall

A Plucked Zither – Phuong T. Vuong

The Diaspora Sonnets by Oliver de la Paz

Fiction

The Dream Builders – Oindrila Mukherjee

She is a Haunting – Trang Thanh Tran

Flux – Jiwoo Chong

Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea – Rita Chang-Eppig

The Brightest Star – Gail Tsukiyama

When the Hibiscus Falls – Evelina Galang

Lei and the Fire Goddess – Malia Maunakea

Holding Pattern – Jenny Xie

Banyan Moon – Thao Thai

Elsewhere – Yan Ge

Excavations – Hannah Michell

The Sorrow of Others – Ada Zhang

Tomb Sweeping – Alexandra Chang

Happiness Falls – Angie Kim

The End of August – Yu Miri

Nonfiction

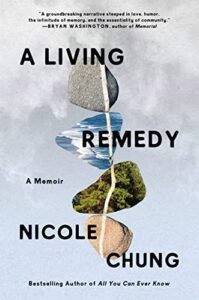

A Living Remedy – Nicole Chung

Black Avatar and Other Essays – Amit Majmudar

Meet Me Tonight In Atlantic City – Jane Wong

Owner of a Lonely Heart – Beth Nguyen

Daughter of the Dragon – Yunte Huang

Interview with Nicole Chung

In this new series of author interviews, THROUGHLINES presents writers with standard questions that reveal where their releases fit in the world of academia.

Nicole Chung is the author of A Living Remedy and All You Can Ever Know. A Living Remedy was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice and has already been named a Best Book of 2023 by Time, Harper’s Bazaar, Esquire, USA Today, and Booklist, among others. Chung’s 2018 debut, the national bestseller All You Can Ever Know, landed on over twenty Best of the Year lists and has been translated into several languages. It was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and NAIBA Book of the Year, a semifinalist for the PEN Open Book Award, a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, and an Indies Choice Honor Book.

Nicole is currently a contributing writer at The Atlantic, a Time contributor, and a Slate columnist, and her writing has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, Esquire, The Guardian, GQ, and Vulture. Previously, she was digital editorial director at the independent publisher Catapult, where she helped lead its magazine to two National Magazine Awards; before that, she was the managing editor of The Toast and an editor at Hyphen magazine. In 2021, she was named to the Good Morning America AAPI Inspiration List honoring those “making Asian American history right now.” Born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, she now lives in the Washington, DC area.

Throughlines: A Living Remedy reads not only as a memoir of your life as a working-class Korean American adoptee, but as an indictment of the American healthcare and labor system writ large. How did you balance these two registers—the personal and intimate with the structural and material—as you wrote?

Nicole Chung: I wish I could point to some specific process or technique, but that’s just how the story needed to be told; I tried to listen as well as I could, and let it guide me. You have to tell the truth in memoir, and the truth is that there was no way to write honestly about my family or our losses without also acknowledging and confronting these systems that failed my parents (as they fail so many others in our country) and led to my father’s early death. And at the same time, I was conscious of not wanting to lecture, or turn this intimate story into a polemic—I think the facts are damning enough, and speak for themselves.

Our personal experiences are always informed and impacted by our upbringing, our family’s situation, our own situation in the world. There’s no way to tell a true personal story without acknowledging the systems and structures we live with. And I’m never interested in telling an intimate story just for the sake of doing so: I think memoir writing is less concerned with the sequence of events in one life than in meeting readers where they are and hopefully providing a space where they can think about their own lives.

Throughlines: This isn’t your first memoir, but the genre has become increasingly popular: I think here of writers like Cathy Park Hong, Michelle Zauner, Hua Hsu. Why do you think Asian American writers today are turning to memoir, and why have you continued writing in this particular genre?

Nicole Chung: I remember when I was writing the proposal for my first book, there were really no comps, at least not close ones. And that was only seven years ago! It’s really exciting to see more Asian American books of all genres on the shelves, but of course that’s not new—we were always here, trying to write about and for our communities, even when our stories were an even harder sell to publishers. As for why there are more visible Asian American memoirists—though there should always be more!—I don’t think what draws us to the form is necessarily different from what draws anyone else to it. It can be a way to ask a question that is important to us, examine or come to terms with the past, seek forgiveness (for ourselves or others), arrive at some new self-understanding, interrogate our choices and our lives with rigor and honesty, even free us from things we have carried for too long. And it can do all of this while, again, reaching out to readers, giving them something to hold onto, encouraging them to think about their own lives—to meet themselves.

Throughlines: As an adult in the book, you grieve how care—for your parents after you move out, for yourself in the wake of their deaths—is often pushed aside in favor of work. Where did you find the space to put care toward this book as it developed?

Nicole Chung: A question that runs through this book is: What does it mean to grieve under capitalism? Is there space for grief at all? And to try to address that question, I really had to be honest with myself about the ways in which I’d often been forced to set aside my own humanity because I was supporting two families and needed to produce and “provide” at all costs.

After my mother died in the spring of 2020, I didn’t work on this book for a long time. I didn’t know if I’d ever be able to finish it—or to rewrite it, really, because I knew that’s what would need to happen. By the time I did start writing again, I had changed. Everyone I knew had. It was grief, it was the pandemic, but it was also just growing older, learning more about myself, realizing I needed to have a different kind of relationship to and with my work. Unlike my process with my first book, I was actually living through some of the events in this book, trying to write about my grief in real time. I had some pieces set, I figured out the ending fairly early on, but I didn’t know how I would get there for quite some time. It was scary, but eventually the fear was joined by curiosity, by wonder, by questions: What was I learning, about myself and my writing, by living through these losses? What was most important to me now? Could I write a book about this grief that would matter to others, possibly even help them feel less alone? I had to trust myself as a writer, and trust the creative process, in a way I really hadn’t before. There was no muscling or powering through this book. It required everything I had, and I suppose it required a kind of surrender, too—an acknowledgment of my limitations, my fears, my grief, my humanity. Which led to a kind of freedom in the work that really surprised me.

At times, I still pushed myself, writing all day, every day, for weeks. But at other times, the work was slow, and I let it be slow. I took breaks when they felt necessary. I tried to pay attention to not only what the book needed, but what I needed in order to write it. It’s nothing especially life-changing or profound, but again, it was all new to me—and nothing like my past work experience as an editor, as a writer. I know this book became what it needed to be, the best version of itself it could be, because I really tried to pay attention to my own needs as I worked on it.

Throughlines: What classes would your book be perfect to be taught in and why?

Nicole Chung: I can see A Living Remedy being taught in a variety of courses—literature, writing (particularly classes or seminars focused on creative nonfiction and/or memoir), Asian American lit, diasporic lit. Given that the book also serves as an invitation to consider our broken healthcare system and the ways in which our country fails many of its most vulnerable, I hope it can be part of conversations around public health and public assistance, elder care and the caregiving crisis, end-of-life issues, community care, and more. I also think that those studying to be counselors, social workers, hospice nurses, or healthcare workers in service of the sick and dying might find it instructive. Finally, as a transracial adoptee, I’m well aware of how few adoptee-authored stories exist; for those social workers and others interested in the growing area of critical adoption studies, the book may be of particular interest.

Throughlines: What themes / ideas in your book make it a good fit for teaching Ethnic Studies, English, or other literature-based courses?

Nicole Chung: In terms of ethnic studies, some relevant topics include immigration, adoption, the intersection of race and class, racial isolation, seeking to reconnect family bonds severed by adoption. I took many literature and writing classes in college and grad school, and in all that time I was only assigned one book by an Asian American woman writer (Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston). There’s such a wealth of contemporary Asian American stories, and regardless of their speciality or area of concentration, English scholars and aspiring writers should have the opportunity to encounter not just one but several in the course of their studies.

Throughlines: How can your book bring new perspectives to students?

Nicole Chung: I’ve heard from many Korean Americans and many adoptees that reading my work is the first time they’ve gotten to see anything like their own experience reflected in literature. From my own experience as a reader, I know that stories can also, in their specificity, help us reconsider larger issues we may already be aware of, as well as problems we are still figuring out how to address—a well-told story can open up a topic for broader discussion, give us new ways into it. In A Living Remedy, I write about my experiences as a Korean American in my white working-class adoptive family, class mobility, invisible poverty, the suffering caused by our inadequate safety net, loss during the pandemic, the importance of community and how we still must try to care for each other. I hope this book helps readers, including students from various backgrounds, consider systemic problems and structural failings and those who suffer because of them, while also being a companion to those who are grieving or living through similar challenges and losses in their families.

Throughlines: What would having your book taught mean to you?

Nicole Chung: I’ve been invited to visit schools and lead writing workshops for students of all ages, from elementary school through graduate school, and I always consider it a great privilege. I’m honored whenever I hear that my writing has been assigned or recommended to learners. It means a lot, particularly because I grew up so rarely seeing anything like my own experience or perspective in the stories I loved.

In this new series, THROUGHLINES compiles trending articles, films, and other media that are relevant to contemporary Asian American literature and culture.

1. Sophia Nguyen’s article “Smithsonian abruptly cancels Asian American literary festival” investigates the abrupt cancellation of the exciting and important Asian American Lit. festival just weeks before it was to take place.

2. Book critic and essayist Andrea Long Chu wins the Pulitzer Prize might the first trans Pulitzer Prize winner

3. Yu and Me Books, in Manhattan’s Chinatown, has been devastated due to a fire, and the community has rushed to its aid.

4. At the Tate Museum, a racist mural by Rex Whistler puts galleries in a bind.

5. After using translations without permission, British Museum Reaches Settlement with Poet Yilin Wang in a law suit.

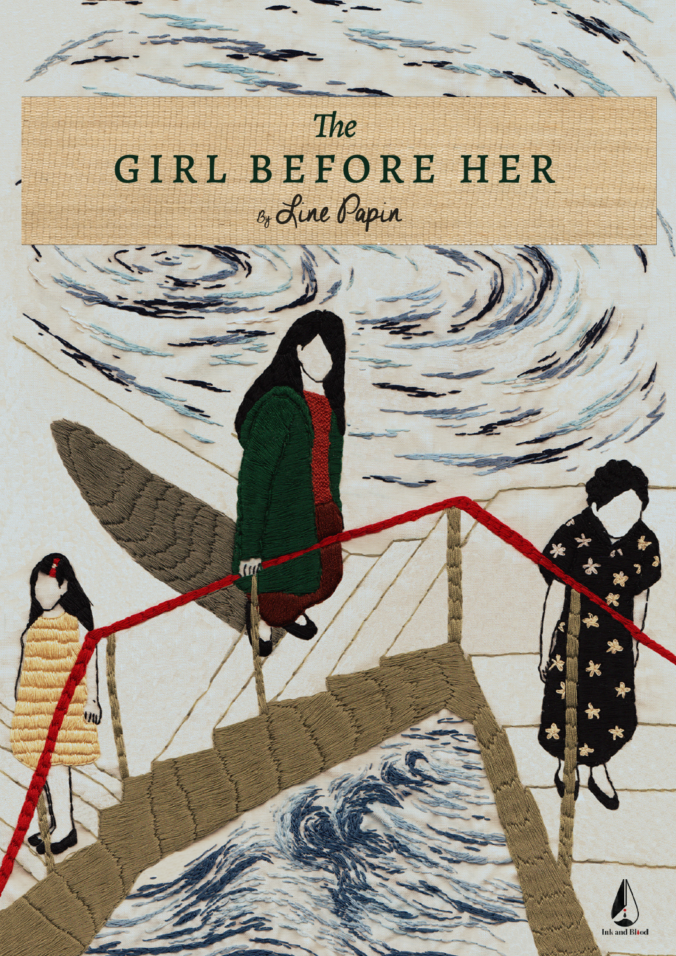

Kaya’s New Release: The Girl Before Her

Line Papin’s English-language debut, the novel The Girl Before Her, is here! This book offers a window into the existential anguish of displacement as experienced by a child on the cusp of becoming a woman. Uprooted without explanation from the sunshine and chaos of Hà Nội at the age of ten, the narrator finds herself adrift in the unfamiliar, gray world of France and grappling with a deep sense of uncertainty about who she is and where she belongs. Part meditation, part family history, part message in a bottle to her younger selves, Papin’s lyrical work of autofiction explores what it takes to embrace one’s multiracial, transnational self by making peace with the generations of women who’ve come before. This book is also the first to be published by Ink & Blood, a new joint imprint from Kaya Press and the Diasporic Vietnamese Artist Network (DVAN), which aims to bring Vietnamese literary voices from across the globe to English readers. Email neela@kaya.com to request desk copies, or purchase here! Stay tuned for Line Papin’s upcoming book tour, and check out upcoming tour dates here.

Leave a Comment

We'd love to know what you think.