Welcome back to THROUGHLINES, Kaya Press’s newsletter that bridges the gap between contemporary Asian Pacific literature and Asian American Studies. In our sixth issue, we invite you to join us at AAAS, and Erica Kanesaka shares her syllabus on cute studies. Our running inventory grows with its sixth installment, highlighting recent publications by API diasporic authors. Hua Hsu also offers insights on how his debut memoir, Stay True, can be read in classrooms for the fourth installment of our author interview series. In the second installment of our new series Endnotes, we compile trending media relevant to contemporary Asian American literature and culture. You can find updates on Kaya Press’s newest release, The Girl Before Her, and information on how to obtain desk copies at the end of this newsletter.

If you have questions or comments for THROUGHLINES, we invite you to email us at neela@kaya.com

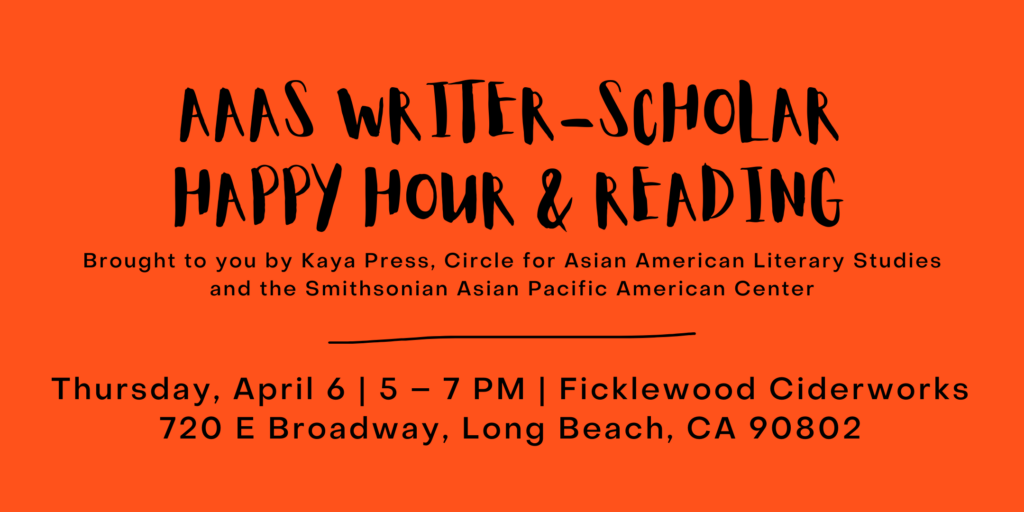

Join us at AAAS!

Come connect with Asian American scholars and writers at this Happy Hour and reading in conjunction with the Association of Asian American Studies 2023 conference in Long Beach! Readings will feature Marie Myung-Ok Lee (The Evening Hero), Sameer Pandya (Members Only), Leland Cheuk (No Good Very Bad Asian), Jen Soriano (Nervous: Essays on Heritage and Healing), Swati Rana and others. To RSVP, click the link here!

Free drink tickets if you sign up for the Kaya Press Throughlines Newsletter! Two free drink tickets if you share a syllabus with Throughlines for our syllabi archive! (More info here!)

Syllabus: Cute Studies

Erica Kanesaka, Emory University

Erica Kanesaka is an Assistant Professor of English at Emory University. An interdisciplinary scholar, she specializes in Asian American literary and cultural studies, with a focus on the racial and sexual politics of kawaii and cuteness. Her other areas of interest include childhood studies, transnational feminisms, feminist disability studies, and feminist science and technology studies. For a full bio, visit her website here.

COURSE DESCRIPTION

This course critically examines the aesthetics of cuteness in the context of the politics of race, gender, sexuality, disability, and age, with a special focus on the globalization of Japanese kawaii (“cute”) culture and its impact on Asian America. In its associations with the small, soft, and simple, cuteness is an aesthetic category intimately bound up in differences of power. Over the past few decades, this aesthetic has been freshly emerging as a global phenomenon in relation to new technologies and the spread of Japanese popular culture.

In this course, we will study literary texts and cultural objects that engage the aesthetic to unpack how cuteness commodifies social difference and distills complex political dynamics within seemingly trivial and mundane aspects of everyday life. We will situate its contemporary popularity in longer histories of imperialism and commodity capitalism, as well as cultural conceptions of Asian people, women, children, and animals.

| Week 1 + 2: Introductions, Cute Studies: A Serious Subject? |

Article: “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garden” (Ngai)

“The Two-Layer Model of ‘Kawaii’: A Behavioral Science Framework for Understanding Kawaii and Cuteness” (Niitono) Excerpt: “Sei Shōnagon’s ‘List of Cute Things'” (Dale) Poem: “Toy Boat” (Vuong) |

| Week 3: Cuteness, Race, and Difference |

Article: “Racist Cute: Caricature, Kawaii-Style, and the Asian Thing” (Bow) |

| Week 4: Power Play: Toys and other Scriptive Things |

Article: “Cuteness and Commodity Aesthetics: Tom Thumb and Shirley Temple” (Merish)

“Dyes and Dolls: Multicultural Barbie and the Merchandising of Difference” (DuCille) Book: The Bluest Eye (“Winter,” “Spring,” and “Summer,” Morrison) |

| Week 5: Sparking Joy: Kawaii Affective Assemblages |

Article: “Feeling Girl, Girling Feeling: An Examination of ‘Girl’ as Affect” (Swindle)

“Kawaii Affective Assemblages: Cute New Materialism in Decora Fashion, Harajuku” (Rose, Kurebayashi, Saionji)

Essay: “KonMarimasu: A Japanese American Incarceration Road Trip” (Yamashita)

TV: “Empty Nesters” (Tidying Up with Marie Kondo)

Book: So Pretty / Very Rotten: Comics and Essays on Lolita Fashion and Cute Culture (Mai, Nguyen)

|

| Week 6: Pink Ice Cream: Sweetness, Sentimentality, Sexuality |

Articles: “Radical Pink: The Aesthetics of Visionary Black Girlhood in Sadie Barnette’s ‘Dear 1968…’ and Black Sky“ (Hernandez)

Essays: “Crying in H Mart” (Zauner)

“In Defense of Saccaharin(e)” (Jamison)

Music videos: “Ice Cream” (BLACKPINK, with Selena Gomez)

“Pynk” (Janelle Monaé)

Website: Baby Talk for Parents

|

| Week 7: Pink Globalization I: From Japanese Schoolgirl Culture to Global Phenomenon |

Book: A Tale for the Time Being (Ozeki)

Articles: “Cute But Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics” (Shiokawa)

|

| Week 8: Pink Globalization II: Queering Kawaii and the Politics of Care |

Book: A Tale for the Time Being (Ozeki)

Articles: “Flexible Femininities? Queering Kawaii in Japanese Girls’ Culture” (Iseri)

|

| Week 9/10: Softening Techno Orientalism: Mukosukei and Mobile Kawaii |

Film: Big Hero 6

Articles: “How Japanese Is Pokémon?” (Iwabuchi)

App: Pokémon Go

|

| Week 11: Artificial Friends I: Dolls and Digital Companions |

Book: Klara and the Sun (Ishiguro)

Articles: “Authenticity in the Age of Digital Companions” (Turkle)

“Dolls” (Cheng, from Ornamentalism)

|

| Week 12: Artificial Friends II: Techno-Orientalism as Technoableism |

Book: Klara and the Sun (Ishiguro)

Essays: “My Cyborg Future” (Wong)

|

| Week 13: Docile or Dangerous?: The Yellow Peril and Cute Monstrosity |

Film: Gremlins

Article: “Yellow Peril, Oriental Plaything: Asian Exclusion and the 1927 U.S.-Japan Doll Exchange” (Kanesaka)

Essay: “Cute. Dangerous. Asian American. ‘Gremlins’ @ 35” (Lee)

|

| Week 14: Cruelty or Affection?: Using Pets, Using People |

Film: Bao

|

| Week 15: Vulnerability or Power?: Angry Little Asian Girls |

Book: Angry Little Girls (Lee)

Articles: “A Killjoy Manifesto” (Ahmed)

|

A List of Recent Books from API Diasporic Writers, September 2022-January 2023

This incomplete list is one in a series of inventories THROUGHLINES is developing as an informal resource for students, researchers and writers to find adjacencies among established and new writers alike. For an updated list of titles, visit: http://kaya.com/throughlines/inventories/.

Poetry

Prescribe – Chia-Lun Chang

Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency – Chen Chen

The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On – Franny Choi

Pink Waves – Sawako Nayakasu

The Rupture Tense – Jenny Xie

Togetherness – Wo Chan

Fiction

Which Side Are You On – Ryan Lee Wong

The Book of Goose – Yiyun Li

Bliss Montage – Ling Ma

Ghost Town – Kevin Chen

3 Streets – Yoko Tawada

Early Light – Osamu Dazai

Funeral – Vi Khi Nao, Daisuke Shen

Saha – Cho Nam-Joo

Weasels in the Attic – Hiroko Oyamada

Age of Vice – Deepti Kapoor

Brotherless Night – V. V. Ganeshananthan

When I’m Gone, Look for Me in the East – Quan Barry

Ghost Music – An Yu

Dead-End Memories – Banana Yoshimoto

The Age of Goodbyes – Li Zi Shu

Nonfiction

Stay True – Hua Hsu

Year of the Tiger: An Activist’s Life – Alice Wong

How Far the Light Reaches – Sabrina Imbler

Superfan: How Pop Culture Broke My Heart – Jen Sookfong Lee

Conversation with Birds – Priyanka Kumar

Making a Scene – Constance Wu

The White Mosque – Sofia Samatar

Interview with Hua Hsu

In this new series of author interviews, THROUGHLINES presents writers with standard questions that reveal where their releases fit in the world of academia.

Hua Hsu is a staff writer at The New Yorker and the author of A Floating Chinaman: Fantasy and Failure Across the Pacific (2016) and the memoir Stay True (September 2022). He is currently working on an essay collection titled Impostor Syndrome. Hsu is a contributor to CBS News’s Sunday Morning; serves on the governance board of Critical Minded, a collaboration between the Ford Foundation and the Nathan Cummings Foundation; and serves as judge for various literary competitions and fellowships, including the PEN America Literary Awards, Rona Jaffe Fellowship, and Dayton Literary Peace Prize. He was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in criticism in 2018 (New Yorker); was a finalist for the James Beard Award for Food Writing in 2013 (for “Wokking the Suburbs,” Lucky Peach); and his work has been anthologized in Best Music Writing (2010 and 2012) and Best African American Essays 2010. Hsu previously wrote for Artforum, The Atlantic, Grantland, Slate, and The Wire; his scholarly work has been published in American Quarterly, Criticism, PMLA, and Genre. He previously taught at Vassar College and was formerly a fellow at the New American Foundation and the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center at the New York Public Library. Professor Hsu’s research and academic interests include Asian American studies, transpacific studies, critical ethnic studies, popular culture and subculture, and literary nonfiction.

Throughlines: You live so many lives as a writer: You’re a critic for The New Yorker, a professor at Bard College (with a monograph, A Floating Chinaman), and now a memoirist. How does Stay True capture these different selves and fields of experience?

Hua Hsu: I’m not sure it captures these different selves in any explicit way—the memoir “ends” roughly around 2002. However it’s written with the benefit of hindsight and perspective, so the seeds of who I would become are all there: the fascination with language, consciousness around the limitations of language, an interest in forgotten or out-of-the-way stories, a desire to exercise critical judgment as a way of forging identity. I sometimes knew these were all part of the same story, but it didn’t become clear to me until I was done.

Throughlines: The way you describe writing—”a way to live outside the present, skipping over its textures and slowness”—feels almost dream-like. Do you experience the same feeling regardless of the genre you’re thinking in? Another way of putting this: How does your relationship with language change when you’re writing academically, critically, personally, if at all?

Hua Hsu: Good question. It did feel somewhat dream-like to write Stay True. I think part of it is that I was channeling feelings or sensations I’d been storing up for decades. Whereas with my criticism or journalism, I’m usually quite measured and in control of the page—I know where things will begin and end. With this book, writing felt very different. I think I was more interested in using language differently, more playfully or even mystically, than when I usually write for an editor/publication.

Throughlines: Friendship plays an invaluable role in your growth as a person in this memoir. How can we—as academics, as writers—change the way we think about community to form connections that leave us changed for the better?

Hua Hsu: I wish I had a more discrete answer for this. I got pretty deep into reading about different theories of friendship, from Aristotle to Derrida. I think Derrida imagines this possibility of friendship as a model for political community which I find quite uplifting, even if I don’t completely understand it myself. But I do think there’s something about the expectations we bring to friends—a desire to see as well as be seen—that suggests more capacious possibilities when it comes to regarding strangers, potential colleagues and comrades, etc.

Throughlines: Stay True describes Asian American as “a messy, arbitrary category,…capacious enough for all of our hopes and energies.” An imperfect and unwieldy question: What are your own hopes for Asian Americans—in academia, the broader literary community, and in general?

Hua Hsu: I think the messiness is okay—it means things are still fairly capacious and open. Rather than trying to draw lines around something fairly arbitrary, we might look toward commonalities, affinities, the differences that can be overcome, in the hope of building something new. Asian Americans, as a category, will continue to grow and evolve in unpredictable ways—in some states, for example, South Asians will soon eclipse those from East Asia as the dominant “Asian” diasporic community. The nature of these changes means we must continue rethinking what this category has meant and can mean in the future. History is a useful guide—it reminds us that we aren’t the first. But that should be an uplifting thing to realize.

Throughlines: What classes would your book be perfect to be taught in and why?

Hua Hsu: That’s such a daunting question! There are some obvious answers to this: Asian American/Ethnic Studies courses, American lit, studies of immigrant culture, literary non-fiction workshops, classes on taste/distinction/identity, classes on youth culture. There are certainly other works/authors I’d love to see Stay True taught alongside: Maxine Hong Kingston, Margo Jefferson, Svetlana Boym, Bryan Washington, Jose Vadi, Gillian Rose, Lucy Sante, Kiese Laymon, Teju Cole.

Throughlines: What themes / ideas / characters / poems / words in your book make it a good fit for teaching Ethnic Studies, English, or other literature-based courses?

Hua Hsu: At a basic level, Stay True is a memoir about self-exploration and self-discovery, what we inherit through lineage and migration, how we piece new worlds together through language and learning. It’s about studying your parents’ accent and wondering when you will surpass them—and why this feels imperative. It’s about the micro-distinctions within communities only familiar to those inside it—in this case, what a second-generation Taiwanese American sees in a Japanese American classmates whose roots in this country are much deeper. And, as it’s set in Berkeley in the nineties, there’s a lot that’s quite literally about the influence that Ethnic Studies classes and encountering people in movements like Critical Resistance had on me as I was trying to figure out who I wanted to become.

Throughlines: How can your book bring new perspectives to students?

Hua Hsu: I stop short of saying that my account of my own life as a student in the late 1990s has a great deal to say about the contours of a young person’s life today. We all face the stresses or challenges unique to our contexts. But I always think it’s useful to learn about other people’s contexts—it makes our own lives feel less lonely. I hope my account of what it was like to study, learn, befriend, be dutiful, and be bored might find resonance with college-age students navigating their own versions of these experiences today.

Throughlines: Does your book feature any experiences, settings, or characters that you wish were better represented in academia?

Hua Hsu: I wasn’t necessarily conscious of this at the time, but many readers have gravitated toward my depiction of friendship, particularly friendship between young men. So I guess that might be a dynamic that’s not as represented in academia?

Throughlines: What other media (tv shows, books, articles, movies) do you think would pair well with your book?

Hua Hsu: The music of Pharoah Sanders, a playlist of 1998 R & B, Berry Gordy’s The Last Dragon.

Throughlines: What would having your book taught mean to you?

Hua Hsu: As someone who teaches, I appreciate the deliberation that goes into crafting a syllabus. It would be a tremendous honor to appear on other people’s (since I would never teach it myself in my own class).

In this new series, THROUGHLINES compiles trending articles, films, and other media that are relevant to contemporary Asian American literature and culture.

1. Kathy Chow’s personal essay “On Loving White Boys” interrogates the racial scripts of desire.

2. Jaime Chu’s dual review “Hong Kong Literature’s Growing Pains” examines the political limits of Anglophonic writing and its questions of postcoloniality and cultural authority.

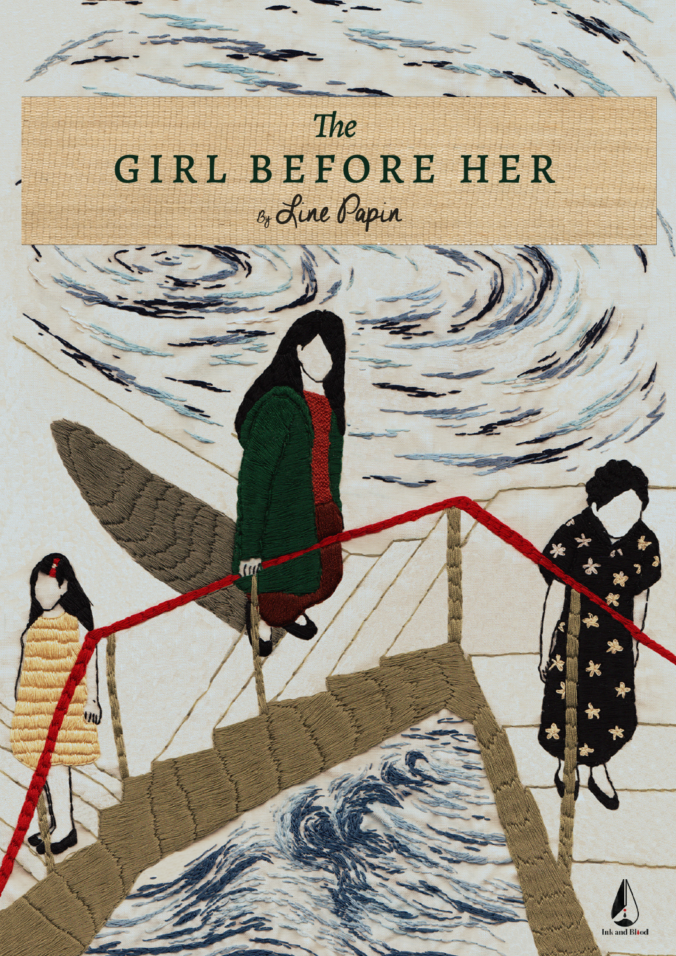

Kaya’s New Release: The Girl Before Her

Line Papin’s English-language debut, the novel The Girl Before Her, is here! This book offers a window into the existential anguish of displacement as experienced by a child on the cusp of becoming a woman. Uprooted without explanation from the sunshine and chaos of Hà Nội at the age of ten, the narrator finds herself adrift in the unfamiliar, gray world of France and grappling with a deep sense of uncertainty about who she is and where she belongs. Part meditation, part family history, part message in a bottle to her younger selves, Papin’s lyrical work of autofiction explores what it takes to embrace one’s multiracial, transnational self by making peace with the generations of women who’ve come before. This book is also the first to be published by Ink & Blood, a new joint imprint from Kaya Press and the Diasporic Vietnamese Artist Network (DVAN), which aims to bring Vietnamese literary voices from across the globe to English readers. Email neela@kaya.com to request desk copies.

Leave a Comment

We'd love to know what you think.