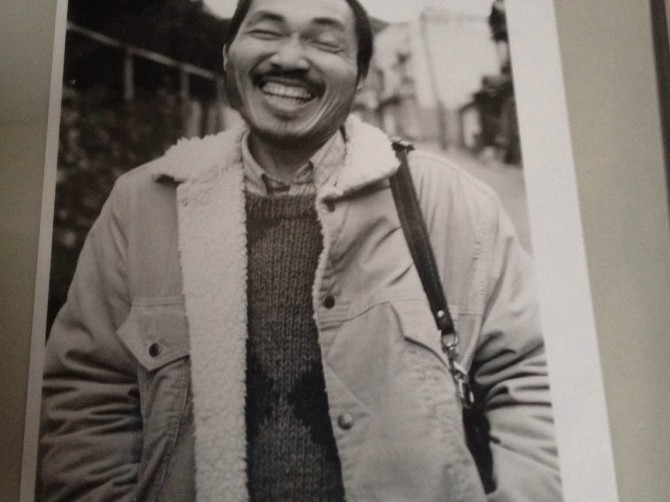

On Sunday, the 26th of October, 2014, renowned artist and writer Akasegawa Genpei (赤瀬川 原平) passed away in a hospital in Tokyo. Akasegawa was the author of Hyperart: Thomasson, which Matt Fargo translated and Kaya Press published in 2010. Best known for his avant-garde art and involvement with Neo-Dadaism, he co-founded the Hi Red Center in 1963 and the Roadway Observation Society in 1986. Akasegawa has also won awards for his literature, including the Akutagawa Prize, the Kōdansha Essay Award, and the Noma Literary Award for New Writers.

—

A Word from the Publisher, Sunyoung Lee

Everything that anyone does is a snapshot of who they are as a person – some kind of telegraphing of their personality or concerns or commitments or preoccupations. But when someone is a writer – when they’ve polished their facility with language so that it becomes more of a window than a wall – we, their readers, are given the rare privilege of getting a direct line into their minds. And, if we’re lucky enough, and open enough, and if causes and conditions line up in just the right way, we can be transformed by that encounter.

I’ve never had the opportunity to physically meet with Akasegawa Genpei – by the time we were publishing his book, he was already quite ill, in addition to being an ocean and multiple islands away. So my only contact with him has been through his writings – specifically, through his book Hyperart: Thomasson – and to be even more precise, through Matt Fargo’s brilliant English-language translation of his work.

But that solitary encounter was all that was needed for some part of his mind to take root in my own. It sits there, quiet and observant, looking with bright, intelligent eyes and not a little humor at everything in my path that I am most likely to pass by without a second glance – doorknobs and doorways, stairways and sidewalk protuberances. It urges me to notice the ways in which even the most easy-to-overlook parts of the world we live in are patiently, silently, and with the utmost sincerity expressing something important worth attending to.

“A spectre is haunting Tokyo – the spectre of Thomasson,” Akasegawa announces at the beginning of Hyperart: Thomasson. “But nobody notices. Or at least they never noticed until now. Even when it stood plastered on the sides of buildings downtown, people just walked on by, oblivious. Every once in a while, someone would bump into it, or get part of it snagged on their sweater. But they still managed to ignore it, detaching their sleeve and continuing on down the street. And yet…”

And yet, someone was paying attention. Someone looked at a stairway that never went anywhere and a gate that was now a blank wall and a doorway three stories up the side of a building and realized that the cities in which we live produce their own art, art made without an artist – and that these seemingly useless objects have something important to say about our world, about the costs and erasures of development, about the persistence of matter in the face of changing ideas.

Then Akasegawa published his observations in a series of articles in a photography magazine and invited anyone paying attention to walk their own streets and share what they discovered there. He took a singular insight and made it a point of commonality – something that everyone willing enough to pay attention and think deeply about what they had observed could participate in – not a principle for exclusion.

Last year, members of the Hyperart Thomasson Observation Society – a group of former students and others who had embraced the ethos of Thomasson observation, sending in photos and commentary – held a 31st anniversary exhibit in a gallery in Shinjuku. Thirty-one years after the first such exhibit, people who had, as young students, been exposed to the power of the idea of Thomassons – who had experienced the joy of trolling the city for their own encounters with the overlooked and under-observed art that that the city itself makes – were still captivated by the ideas they discovered through Akasegawa. That, more than the recent exhibits of Akasegawa’s work (in the Venice Biennale’s Japan Pavilion, at the Chiba Museum), is a testament the power of Akasegawa’s work and its ability to inspire.

Hyperart: Thomasson is actually only one tiny part of what Akasegawa has done in his life. And in fact, most of the articles we’ve been able to find about his passing are about other, much more “historically” significant contributions he made to the world of art – including the infamous incident where he took the opportunity afforded by a humorless Japanese government’s decision to prosecute him for forgery after he printed a 1000 yen note to turn a courtroom into an art happening. (He ended up being convicted of the crime, but he transformed the courtroom with performances by his friends, exhibits of art, etc. Even with the full weight of the criminal justice system seeking to force him into quiescence, he chose to turn the trial on its head as a way of getting deeper into the question of what art is and can be and why such questions matter.) And that’s not even getting into his popular success as a writer of books that revealed the power of getting older and new ways of looking at over-exposed, museum-bound art masterpieces.

But, as I said, Hyperart: Thomasson is the one work by him that I’ve had the privilege to read. So it’s the only way that I can say that I really, directly know him. And even that little glimpse has been transformative – like putting your hand up to someone’s skin and feeling their heart pulsing through it. The generosity and humor and endlessly surprising intelligence I’ve found there is not just palpable, it’s alive – and, I hope, will continue to live inside me.

Yesterday, Akasegawa Genpei died after a long struggle with illness. Long live Akasegawa Genpei. May we all strive to be part of his after-life.

—

A Word from the Translator, Matt Fargo

There is a certain feeling you get, when you “discover” an artist that you were unaware of. It’s a feeling that I experienced a lot in high school and college:

“Holy shit there was this artist named Chris Burden and he literally SHOT HIMSELF in the shoulder as an art piece!”

“And the whole time Vito Acconci was lying underneath the gallery floor and masturbating while imagining the people in the gallery above him!”

“And this guy Charles Ray made eight hyperrealistic sculptures of himself all having an orgy together!”

The sort of art that gave me this feeling usually occupied some sort of legal or conceptual grey area, caused some sort of problem. As I grew older, of course, these sorts of discovery grew less and less frequent, and I began cultivating a pompous air of “nothing under the sun.” It happens to the best of us, as they say, and unfortunately it even happens to mediocre folk like myself:

“Laurie Anderson did that in like 1968, so…”

“You’re can’t be more Damian Hirst than Damian Hirst, so…”

“I’m actually friends with the curator, so…”

Maybe I would have continued cultivating my disinterest until cultivated disinterest itself lost its appeal; perhaps I would have moved on to outright disdain, become more Dave Hickey than Dave Hickey; for all I know my sentences might have all simply consisted of one one gigantic, rhetorical “so…”

But I will never know, because I discovered Akasegawa Genpei.

Akasegawa was a tremendously influential artist. The performance art he created in the 60s with High Red Center piqued the curiosities of aspiring avant garde-ists around the world. He produced art out of copies of 1000-yen bills, provoking a counterfeiting trial that obliged the court to publicly wrestle with the same issue that artists had been struggling with for centuries: what legally defined “art?”

Essentially, he made a performance piece out of the legal process. The art world watched, agape, tacitly jealous. It was the perfect crime.

And then came the Thomassons—weird pieces of architecture around the city that served no purpose whatsoever, and yet were still being preserved for some mysterious reason: staircases that lead to nowhere, eaves that protected empty walls from the rain, doors up on the third story of a building with no steps leading up to them. Walking around the city and looking for Thomassons became a form of conceptual art for the masses, a public art practice.

This was Akasegawa’s genius: the work he created didn’t consist of objects so much as discourses. Each new turn his career didn’t merely result in new work—it resulted in a brand new genre, with a broad and active group of participants. Yoko Ono perhaps put it best when she said that “Mr. Akasegawa is the kind of artist who inspires everybody every time he makes a new piece of art.”

His magic certainly worked on me. Through Akasegawa Genpei, I learned to see the world differently, to glean that thrilling sense of discovery from an oddly-parked car or a felicitous pattern of bird-droppings. The insular art discussion that I had been stuck in for so many years no longer mattered because Akasegawa had empowered me to create my own discourses. When my curiosities moved on, I could simply change the discourse, as Akasegawa did again and again throughout his career.

This is an artist who moved seamlessly from Neo-Dada happenings to Butoh, then on to performance art, sculpture, Garo comics, prize-winning novels, sketches of Nikon cameras, long-form essays, impressionistic oil painting, Thomassons, Modernology, archives of the literary work of Miyatake Gaikotsu, close-readings of dictionaries, Street Observations, fine-art criticism and a hundred other things. He made a career out of career changes, and in doing so changed the world, and in doing so changed me.

—

Photos taken on October 9, 2014 at the Tokyo studio of Iimura Akihiko, photographer of the spectacular bird’s-eye shot of the “Defunct Chimney” in Azabu, member of the Thomasson Observation Center, and current keeper of the Thomasson archives. That arm in a blue shirt belongs to Iimura-san. The group still meets every month to go over new submissions.

Leave a Comment

We'd love to know what you think.